Code Walkthrough - RAG with LangChain

I recently stumbled upon the “RAG From Scratch” tutorial by LangChain. The tutorial is a great resource for anyone looking to quickly come up to speed with RAG. It covers a lot of ground quite quickly, but in doing so, it skips over some interesting features and in-depth code explanations. That’s where this blog post focuses.

In this article, I’ll briefly explain what RAG and LangChain are. Then I’ll dive into the code of a simple PDF Q&A chatbot application I’ve built based on the knowledge I gained from the LangChain tutorial. If you’ve ever debugged code step by step, checking each line, variable, and argument, and you’ve liked it, then stick around, because that’s exactly what we’re going to do.

If you want to follow along, the prerequisites are

- Familiarity with Python.

- A high-level understanding of RAG.

I’m working on an article with resources about this. - An OpenAI API key.

- A small budget (≤1USD) in OpenAI to be able to call embedding and chat completion models.

I’m also working on an alternative that won’t require an OpenAI API key or a budget on OpenAI. Once it’s ready, I’ll add a link at the end.

LangChain in a Nutshell

In this article/tutorial, we will be using LangChain. LangChain is an open-source framework that makes it easy to develop applications with LLMs. It’s available in Python and Javascrript, and serves as a generic interface for (m)any LLMs. LangChain essentially, makes it easy to compare foundation models with minimal code changes, and allows for easy communication between the different components of an LLM application.

High-Level Overview

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s take a deep dive into our specific use case. My goal when coding this application was to familiarize myself with RAG using LangChain. I’ve also recently worked with Streamlit, so I decided to incorporate it as well.

The result I had in mind was something like this

The main components here are

- The UI: designed in Streamlit.

- PDF indexing: That is the first fun part, where documents are indexed using embeddings. These embeddings are then used to calculate similarities to the user’s question.

- LLM reply: The LLM uses the most similar documents to answer the question.

Now let’s examine all three parts. I’ll be using the following two publications to explain how the RAG application works:

- In-Context Freeze-Thaw Bayesian Optimization for Hyperparameter Optimization

- Transformers Can Do Bayesian Inference

Code along: Streamlit Setup

Streamlit is an open-source Python library that makes it easy to create and share custom web applications by enabling rapid prototyping. I won’t go over all the details here. Instead, we’ll learn by doing.

Let’s start by setting up a backbone for our application. We’ll include a title with the st.title method and a way for users to upload PDF documents. The LLM will use these documents later to answer questions. We’ll use the st.file_uploader method and set the accept_multiple_files argument to true.

import streamlit as st

st.set_page_config(

page_title="PDF Q&A with RAG",

page_icon="📄",

layout="wide"

)

st.title("📄 PDF Q&A with RAG")

st.markdown(

"Upload one or more PDFs to be indexed. Then ask questions about their content."

)

uploaded_files = st.file_uploader(

"Upload PDF files", type=["pdf"], accept_multiple_files=True

)

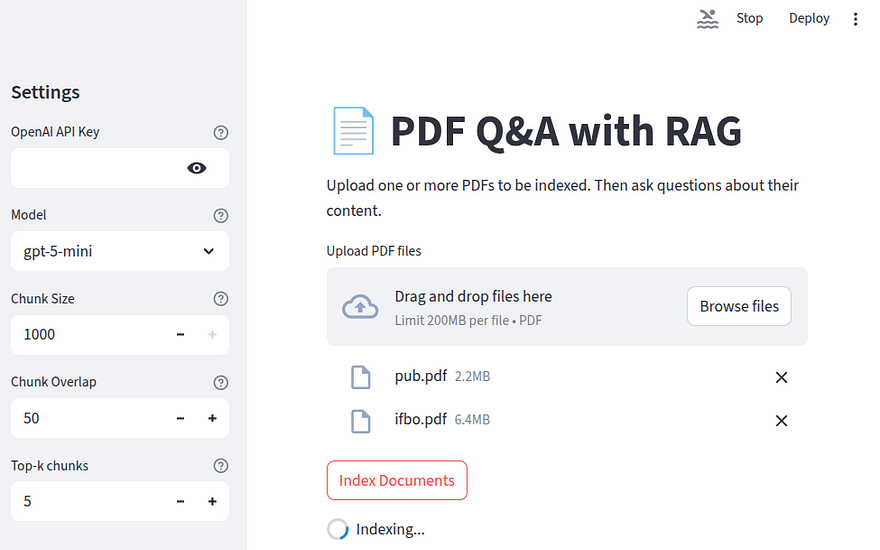

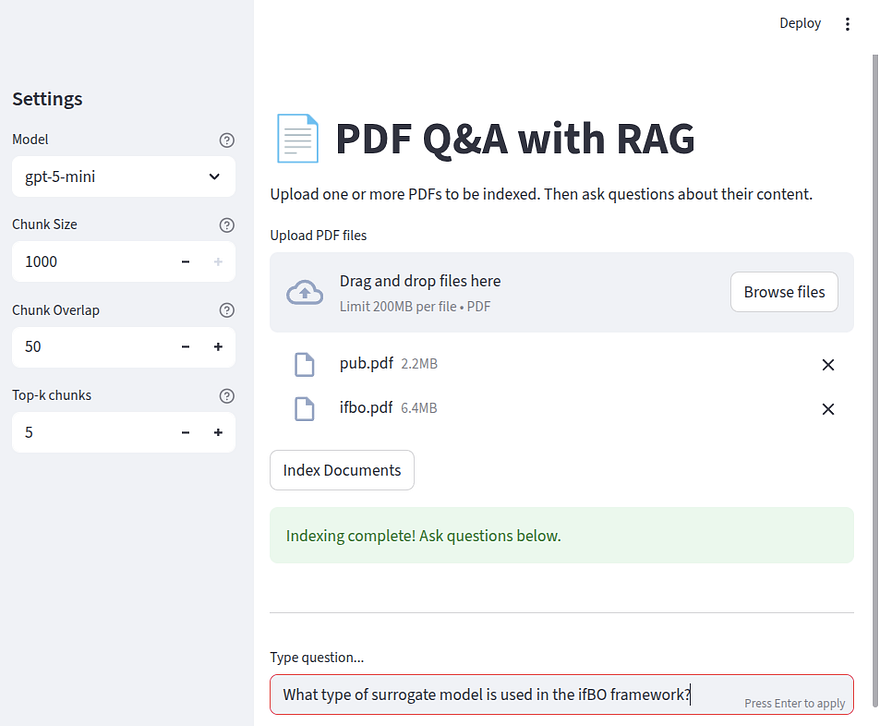

At this point, our landing page looks like this:

As I mentioned earlier, we are going to use OpenAI models for this application. So let’s go ahead and add a configuration sidebar to our application where the users can enter their OpenAI API key and select the model they want to use by appending the following

import streamlit as st

st.set_page_config(

page_title="PDF Q&A with RAG",

page_icon="📄",

layout="wide"

)

st.title("📄 PDF Q&A with RAG")

with st.sidebar:

st.header("Settings")

openai_api_key = (

st.text_input(

"OpenAI API Key",

type="password",

help="Needed only to access OpenAI models.",

)

)

model_name = st.selectbox(

"Model",

options=[

"gpt-4.1-nano",

"gpt-4.1-mini",

"gpt-5-nano",

"gpt-5-mini",

],

index=3,

help="Select the model to use for question answering.",

)

st.markdown(

"Upload one or more PDFs to be indexed. Then ask questions about their content."

)

uploaded_files = st.file_uploader(

"Upload PDF files", type=["pdf"], accept_multiple_files=True

)

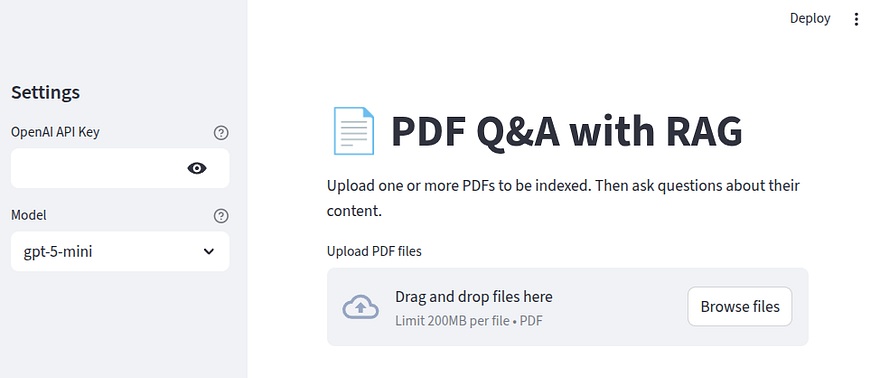

Our landing page should now look like this

Now, let’s take a step back and discuss some RAG-related details, namely indexing, splitting, encoding, and vector stores.

Theory: PDF Indexing and Splitting

In order for our LLM to answer questions based on our documents, it must have access to an external pool of resources. These are what LangChain calls indices.

The first step in building these indices is loading the PDF into Python to extract the text. I used the pypdf library, which is a free, open-source Python library to process PDFs.

# EXAMPLE CODE, NOTE NECESSARY FOR OUR APP

from pypdf import PdfReader

# This gives you a PDF Reader object with some interesting properties

reader = PdfReader("ifbo.pdf")

# you can get the number of pages

print(f"Number of pages: {len(reader.pages)}\n")

# as well as the pdf text

print(reader.pages[0].extract_text())

Number of pages: 27

In-Context Freeze-Thaw Bayesian Optimization

for Hyperparameter Optimization

Herilalaina Rakotoarison * 1 Steven Adriaensen * 1 Neeratyoy Mallik * 1

Samir Garibov 1 Edward Bergman 1 Frank Hutter 1 2

Abstract

With the increasing computational costs asso-

ciated with deep learning, automated hyperpa-

rameter optimization methods, strongly relying

on black-box Bayesian optimization (BO), [...]

Each page must to be embedded to obtain a vector representation, and each embedding is stored in a vector store. Since we will be using LangChain, the next step is to create a LangChain Document.

A Document is an object that stores a piece of text with additional metadata that we want to associate with it. The Document class requires a page_content string containing the text of the document, and offers a couple of optional arguments. Here we will use the metadata optional dictionary argument to pass information such as the page number and the name of the document. This information coul be useful if we decide to print it for the end users, along with the LLM’s answer to their question.

# EXAMPLE CODE, NOTE NECESSARY FOR OUR APP

from langchain_core.documents import Document

# Initialize an empty list that will hold the LangChain Documents for each page

docs = []

# if the PDF document includes metadata,

# and if those metadata include the title, we can also include

# it in our Document with reader.metadata.title

title = reader.metadata.title if reader.metadata.title else "unknown"

# Iterate over the pages

for i, page in enumerate(reader.pages):

# Get the text for th

text = page.extract_text()

docs.append(

Document(page_content=text, metadata={"source": f"{title}, page {i+1}"}))

# See what the first document looks like

print(docs[0])

page_content='In-Context Freeze-Thaw Bayesian Optimization

for Hyperparameter Optimization

Herilalaina Rakotoarison * 1 Steven Adriaensen * 1 Neeratyoy Mallik * 1

Samir Garibov 1 Edward Bergman 1 Frank Hutter 1 2

Abstract

With the increasing computational costs asso-

ciated with deep learning, automated hyperpa-

rameter optimization methods, strongly relying

on black-box Bayesian optimization (BO), face

limitations. [.....]',metadata={'source': 'In-Context Freeze-Thaw Bayesian Optimization

for Hyperparameter Optimization, page 1'}

The pipeline

- PDF → Load with

pypdf→ Convert to LangChainDocument

will be executed for all the PDFs we want to index.

Now that PDFs are loaded as LangChain Document’s, the next step is to split them. The necessity to split the documents arises from the fact that embedding models have a limited context window. Without splitting the documents, any token larger than the context window would essentially be lost. Additionally, retrieval works best when our vector store contains small-ish chunks of documents, because with larger documents, similarity calculations might become a bit fuzzy.

To split each document into smaller chunks, we use the RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter from LangChain. As its name suggests, this splitter recursively tries to split the text using different characters until it finds one that works.

We initialize the splitter as

# EXAMPLE CODE, NOTE NECESSARY FOR OUR APP

from langchain_text_splitters import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

# for demonstrative purposes, chunk size and chunk overlap

# are quite small here

chunk_size=500, chunk_overlap=50

)

# Split all docs into chunks

# remember that at this point 1 doc == 1 page on the original PDF

chunks = splitter.split_documents(docs)

print(f"Number of chunks: {len(chunks)}") ## -> should print 181

chunk_sizespecifies the number of characters that will be included in each split.chunk_overlapindicates how many characters from the end of one chunk will be included as the beginning of the next one. This helps mitigate the loss of information if relevant parts of the text end up in different chunks.

Each resulting chunk is still a LangChain Document and we can inspect its page_content to see how chunk_overlap works.

print(f"Document 1:\n{chunks[1].page_content}\n")

Document 1:

scarce resources incrementally to different con-

figurations. However, the frequent surrogate

model updates inherent to this approach pose

challenges for existing methods, requiring re-

training or fine-tuning their neural network sur-

rogates online, introducing overhead, instability,

and hyper-hyperparameters. In this work, we

propose FT-PFN, a novel surrogate for Freeze-

thaw style BO. FT-PFN is a prior-data fitted

network (PFN) that leverages the transformers'

And if we also investigate the second chunk, we get

print(f"Document 1:\n{chunks[2].page_content}\n")

Document 1:

network (PFN) that leverages the transformers'

in-context learning ability to efficiently and re-

liably do Bayesian learning curve extrapolation

in a single forward pass. Our empirical analysis

across three benchmark suites shows that the pre-

dictions made by FT-PFN are more accurate and

10-100 times faster than those of the deep Gaus-

sian process and deep ensemble surrogates used

in previous work. Furthermore, we show that,

when combined with our novel acquisition mech-

We can see that the end of chunk 1 also marks the beginning of chunk 2.

Theory: Encoding & Vector Stores

Now that we have small, manageable splits, the next step is to calculate the embedding of each split and save it to a vector store. An embedding is a vector representation of the text, and a vector store essentially acts as a database where we can store these vector representations and quickly perform similarity-based retrieval.

For this application, I used the OpenAPIEmbeddings from LangChain with the text-embedding-3-small model. If you are following along, make sure to check what the latest embedding model suggestion is from OpenAI, because models are quickly being marked as legacy.

LangChain offers many different vector store architectures, which you can find here. Personally, I went with FAISS, but I don’t have any strong personal preferences or guidance to offer.

Note that FAISS may be excessive for this simple application. I chose it mainly because I wanted to experiment with it. One could also implement the similarity search from scratch using cosine similarity between the embedding vectors.

To build the vector store and get back a retriever

from langchain_community.vectorstores import FAISS

from langchain_openai import OpenAIEmbedding

# build the vector store using OpenAIEmbeddings

vectorstore = FAISS.from_documents(

chunks,

OpenAIEmbeddings(

model="text-embedding-3-small"

)

)

# build the retriever object

retriever = vectorstore.as_retriever(

search_type="similarity",

search_kwargs={"k": 3}

)

I used the from_documents method, which accepts a list of documents and an embedding function. Finally, I created a vector store retriever object with the as_retriever method. This object can take a string query as an input, and return a list of the most similar documents. The number of documents we want to retrieve is defined by the k parameter of search_kwargs . I defined similarity as the search_type . All the possible options are:

similarity→ Returns thekmost similar documents.similarity_score_threshold→ Returns the documents with a similarity score equal to or higher thanscore_threshold(passed as a keyword argument).mmr→ Selects documents based on the maximal marginal relevance algorithm.

Code along: Back to our ChatBot

Moving back to our application, it would be useful to allow users (and at this point ourselves) to experiment with different settings for the chunk size, the chunk overlap, and the number of similar chunks to retrieve for context. Let’s add those variables to the configuration sidebar like so

import streamlit as st

st.set_page_config(

page_title="PDF Q&A with RAG",

page_icon="📄",

layout="wide"

)

st.title("📄 PDF Q&A with RAG")

with st.sidebar:

st.header("Settings")

openai_api_key = (

st.text_input(

"OpenAI API Key",

type="password",

help="Needed only to access OpenAI models.",

)

)

model_name = st.selectbox(

"Model",

options=[

"gpt-4.1-nano",

"gpt-4.1-mini",

"gpt-5-nano",

"gpt-5-mini",

],

index=3,

help="Select the model to use for question answering.",

)

chunk_size = st.number_input(

"Chunk Size",

min_value=500,

max_value=1000,

value=1000,

step=50,

help="Size of text chunks to split the document into.",

)

chunk_overlap = st.number_input(

"Chunk Overlap",

min_value=0,

max_value=200,

value=50,

step=10,

help="Number of overlapping characters between chunks.",

)

k = st.number_input(

"Top-k chunks",

min_value=1,

max_value=20,

value=5,

step=1,

help="Number of top similar chunks to retrieve for context.",

)

st.markdown(

"Upload one or more PDFs to be indexed. Then ask questions about their content."

)

uploaded_files = st.file_uploader(

"Upload PDF files", type=["pdf"], accept_multiple_files=True

)

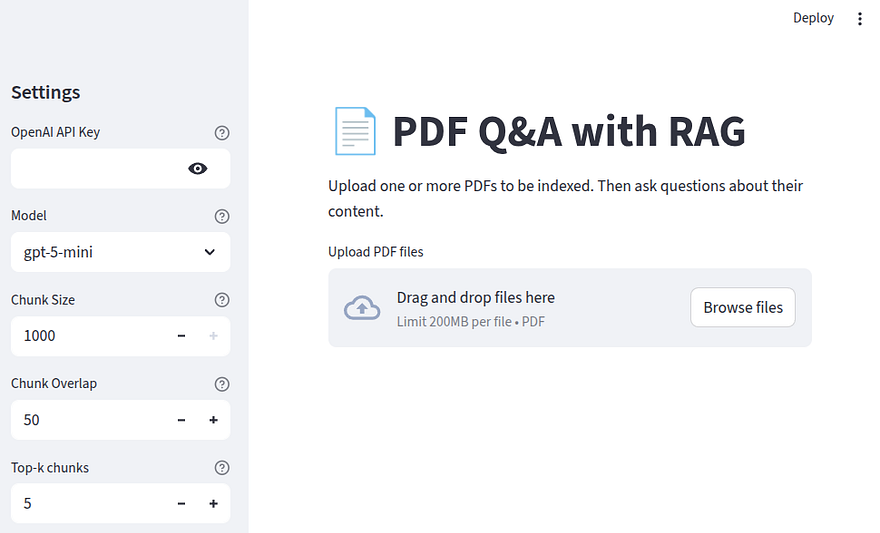

At this point, our landing page looks like this:

Based on what we’ve discussed so far, let’s also code some helper functions. The first function should read the PDFs and return a list of LangChain Document’s

from pypdf import PdfReader

from io import BytesIO

from langchain_core.documents import Document

def read_pdf(file):

# streamlit files have a 'name' attribute

filename = getattr(file, "name", "uploaded_file.pdf")

data = file.read()

reader = PdfReader(BytesIO(data))

documents = []

for i, page in enumerate(reader.pages):

text = page.extract_text()

metadata = {"source": filename, "page": i + 1}

documents.append(Document(page_content=text, metadata=metadata))

return documents

Let’s also add a helper function that takes the list of documents and the setup for chunk size, chunk overlap, and the number of similar documents as arguments. It will return a vector-store retriever that we later query for the most similar passages to use as context in our RAG application.

import tiktoken

from langchain_text_splitters import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

from langchain_openai import OpenAIEmbeddings

from langchain_community.vectorstores import FAISS

def build_index(docs, chunk_size, chunk_overlap, k):

splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

chunk_size=chunk_size, chunk_overlap=chunk_overlap

)

splits = splitter.split_documents(docs)

enc = tiktoken.encoding_for_model("text-embedding-3-small")

total_tokens = sum(len(enc.encode(chunk.page_content)) for chunk in splits)

print(f"Total chunks: {len(splits)}, total tokens: {total_tokens}")

vectorstore = FAISS.from_documents(splits, OpenAIEmbeddings(model="text-embedding-3-small"))

# create a vectorstore retriever

# https://python.langchain.com/api_reference/core/vectorstores/langchain_core.vectorstores.base.VectorStoreRetriever.html

return vectorstore.as_retriever(search_type="similarity", search_kwargs={"k": k})

Code along: Vector Store & Chain

In summary, we have seen how to index and split the PDF documents, and how to encode them and load them in a vector store. We have also defined some helper functions to read the uploaded PDFs and build a vector store retriever. Now, let’s define the other necessary elements before combining everything into a chain.

First though, let’s perform a small optimization that will improve the performance of our application. Streamlit is designed to rerun the entire script from top to bottom each time a user takes an action. This means that we could end up with an application that tries to initialize the LLM, the prompt, and generate the indices every time a user asks a question. So we need of a way to remember such objects for subsequent runs, and avoid re-initializing them.

This is where the st.session_state comes in. It acts as a persistent dictionary that stores variables (i.e., expensive objects) for the current user’s session, ensuring that they are only created once per user session, making our app more efficient.

We define the session state like this

# copy-paste in main.py under

# uploaded_files = ...

state = st.session_state

state.setdefault("retriever", None)

state.setdefault("sources", None)

state.setdefault("prompt", None)

state.setdefault("llm", None)

First, we create an alias state for st.session_state to make the code a bit cleaner. Then, we use the setdefault method to check if a key already exists in the dictionary. In the first run, if the key does not exist, the value will be set to None. In any subsequent runs, if the key already exists (because we populated it later in the script) setdefault will just preserve the existing, initialized object.

The LLM

Now, let’s start defining each component of our RAG application, beginning with the LLM. Remember that the LLM name is saved in the model_name value set from our configuration sidebar. We can initialize the LLM object as follows:

from langchain_openai import ChatOpenAI

if state.llm is None:

state.llm = ChatOpenAI(model=model_name, temperature=0)

Defining the prompt

Now, let’s define the prompt. This is the instruction that we’ll pass to the LLM. Although we could easily come up with a prompt ourselves; however, LangChain offers some community-developed, optimized prompts that work best for particular applications. In our case, we’ll use the rlm/rag-prompt one which looks like this:

ChatPromptTemplate(

input_variables=['context', 'question'],

input_types={},

partial_variables={},

metadata={'lc_hub_owner': 'rlm', 'lc_hub_repo': 'rag-prompt', 'lc_hub_commit_hash': '50442af133e61576e74536c6556cefe1fac147cad032f4377b60c436e6cdcb6e'},

messages=[

HumanMessagePromptTemplate(

prompt=PromptTemplate(

input_variables=['context', 'question'],

input_types={}, partial_variables={},

template="You are an assistant for question-answering tasks.

Use the following pieces of retrieved context to answer

the question. If you don't know the answer, just say that

you don't know. Use three sentences maximum and keep the

answer concise.\nQuestion: {question} \nContext: {context}

\nAnswer:"), additional_kwargs={}

)

]

)

The part we mostly care about is:

"You are an assistant for question-answering tasks.

Use the following pieces of retrieved context to answer

the question. If you don't know the answer, just say that

you don't know. Use three sentences maximum and keep the

answer concise.\nQuestion: {question} \nContext: {context}

\nAnswer:")

To define the prompt, we’ll add the following code below the LLM definition:

from langchain import hub

if state.prompt is None:

state.prompt = hub.pull("rlm/rag-prompt")

Defining the chain

Now, let’s define one of the most interesting parts of the code, the part that reads the uploaded PDFs and builds the vector store retriever, as well as the chain that will handle most of the heavy lifting later.

from utils import read_pdf, build_index

# Copy-paste after the prompt definition

if state.prompt is None:

state.prompt = hub.pull("rlm/rag-prompt")

if uploaded_files and st.button("Index Documents"):

with st.spinner("Indexing..."):

all_docs = []

for file in uploaded_files:

try:

docs = read_pdf(file)

all_docs.extend(docs)

st.toast(f"Indexed {getattr(file, 'name', 'file')} ✅")

except Exception as e:

st.toast(

f"Error processing {getattr(file, 'name', 'file')}: {e}", icon="❌"

)

if not all_docs:

st.warning("No valid documents found in the uploaded files.")

state.retriever = None

else:

state.retriever = build_index(all_docs, chunk_size, chunk_overlap, k=int(k))

state.sources = sorted(list({d.metadata["source"] for d in all_docs}))

state.chain = (

{"context": state.retriever | RunnableLambda(format_docs),

"question": RunnablePassthrough()}

| state.prompt

| state.llm

| StrOutputParser()

)

st.success("Indexing complete! Ask questions below.")

elif state.retriever:

st.success("Indexing complete! Ask questions below.")

Note that we import read_pdf and build_index from the utils.py helper file. That’s a personal preference to keep the code clean. We could also just place those function definitions in main.py (though I’d advise against that).

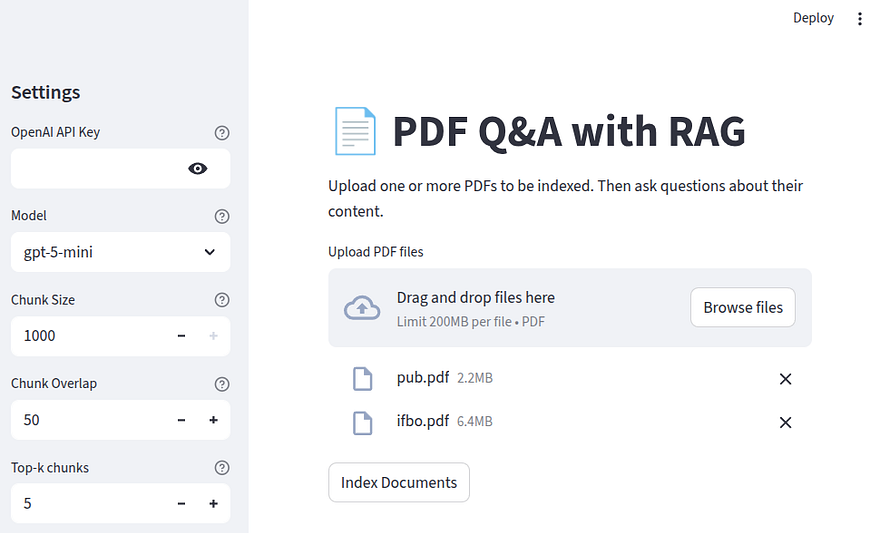

Let’s quickly unpack what this piece of code does. First, notice that as soon as we upload at least one document in our application, an “Index Documents” button appears.

Our if condition checks if any uploaded_files exist and if the Index Documents button has been pressed. Then, to create the impression that work is happening behind the scenes, we instantiate a st.spinner element from Streamlit, and for each document, we try to read_pdf it and append the result to the all_docs list. This is what indexing looks like in the front-end of our application:

Notice the spinning element at the end; that’s what st.spinner does.

Once the indexing is complete, the message Indexing complete! Ask questions below. will appear. Next, we populate the retriever using the build_index helper function. Remember that this function creates our vector store using the user-defined settings from the configuration sidebar.

After that, we build a chain, which lies at the core of our workflow. This step that combines the vector store, the prompt, and the LLM that generates answers to user questions. Let’s examine this part more closely.

from langchain_core.runnables import RunnablePassthrough, RunnableLambda

from langchain_core.output_parsers import StrOutputParser

state.chain = (

{"context": state.retriever | RunnableLambda(format_docs),

"question": RunnablePassthrough()}

| state.prompt

| state.llm

| StrOutputParser()

)

The first part of the chain:

{

"context": state.retriever | RunnableLambda(format_docs),

"question": RunnablePassthrough()

}

is the context retrieval part, the R in RAG. This section is a dictionary mapping in LangChain Expression Language (LCEL) that generates input for the next step state.prompt. The dictionary mapping performs the following two steps:

-

It passes the question through the

RunnablePassthrough()function which simply takes the question that is passed to the chain when the chain is invoked later, and assigns its value to thequestionkey. -

It retrieves and formats the context. The

state.retrieverpart is the heart of the retrieval. It takes the user’s question, which will be passed to the chain when the chain is invoked later, and retrieves thekmost similar documents from the vector base. Next, we pass the retrieved list of documents through theRunnableLambda(format_docs)method. This method essentially creates a list of the LangChainDocumentobjects as a single string of text to be passed as the context. Here’s the definition of theformat_docshelper function:

def format_docs(docs):

# nice, citeable context string

return "\n\n".join(

f"[{d.metadata.get('source','?')} p.{d.metadata.get('page','?')}] {d.page_content}"

for d in docs

)

The next steps in the process are pretty self-explanatory. In a nutshell, the process involves passing the dictionary mapping of the context and question to the prompt, then passing the prompt to the LLM, and then use the StrOutputParser which converts the LLM output into a clean Python string. Without the StrOutputParser, the chain would return the LLM’s complex output, which contains a lot of unnecessary information. For the record, output from a chain without the StrOutputParser would look like this:

{

"content": "ifBO uses FT-PFN - a neural-network-based freeze-thaw probabilistic forecasting network (a PFN) as its surrogate model. This learned model predicts learning curves and is used together with the MFPI-random acquisition function.""additional_kwargs": {

"refusal":NULL

}

"response_metadata": {

"token_usage": {

"completion_tokens": 376

"prompt_tokens": 1356

"total_tokens": 1732

...

"input_token_details": {

"audio": 0

"cache_read": 0

}

"output_token_details": {

"audio": 0

"reasoning": 320

}

}

}

Code along: Invoking the chain

Now we can finally add the code that invokes the chain:

# copy-paste under the elif state.retriever check

from langchain_community.callbacks.manager import get_openai_callback

from utils import format_docs

st.divider()

if state.retriever:

question = st.text_input("Type question...")

if question:

with st.spinner():

with get_openai_callback() as cb:

answer = chain.invoke(question)

print(f"Total Tokens: {cb.total_tokens}, Prompt Tokens: {cb.prompt_tokens}, Completion Tokens: {cb.completion_tokens}, Total Cost (USD): ${cb.total_cost:.6f}")

if not answer:

st.error("No answer returned from the model.")

else:

st.markdown("💡 Answer")

st.write(answer)

Now, let’s unpack what happens in the final part of our code. First, we define a simple st.divider which draws a horizontal line to make the division between indexing and Q&A easier on our application page.

If all went well with the retriever, then we add a text input for the user questions with st.text_input. This is what our application page would look at this stage, with a simple question about one of the indexed publications.

Once we hit enter, the most important and interesting part happens, which is the invocation of the chain by answer = chain.invoke(question). Then, the answer appears.

Conclusion

Throughout the article, I only imported the necessary libraries when they were needed. If you are coding along, make sure to import everything cleanly at the top. You can also find the code in this repo. That’s all from me for this article. I hope you enjoyed it. Till next time…